Nik Lomax, University of Leeds

Many of the analyses of why a majority of British voters opted to leave the European Union in a referendum in June 2016, have pointed to a desire to control immigration as a key driving factor. However, surveys since the referendum show fewer people are now concerned about the issue than they were before the poll.

But what has actually happened to immigration in the three years since the UK voted for Brexit?

Decline in net migration

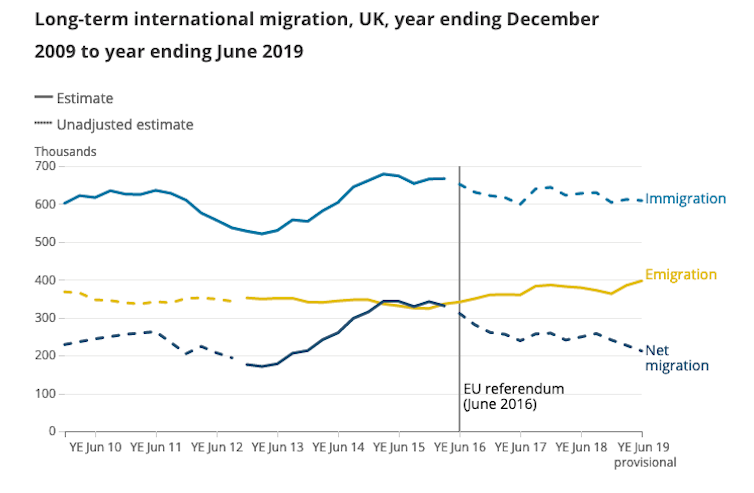

The latest migration estimates published by the Office for National Statistics (ONS) show a steady decline in net migration – the number of immigrants entering the country minus number of emigrants leaving the country – in the three years since the EU referendum in 2016.

The UK saw a net gain of 311,000 migrants in the year to June 2016, which dropped to a net gain of 212,000 migrants in the year to June 2019. This means that while more people are still arriving in the UK than leaving it, the net figure has gone down.

This trend is driven by both sides of the equation. Alongside a decline in the number of people immigrating to the UK – which fell from 652,000 to 609,000 per year in the three year period – the number of people emigrating rose from 341,000 to 397,000. However, the headline figure masks substantial differences between migration from within and outside the EU during this time.

Increase from outside the EU

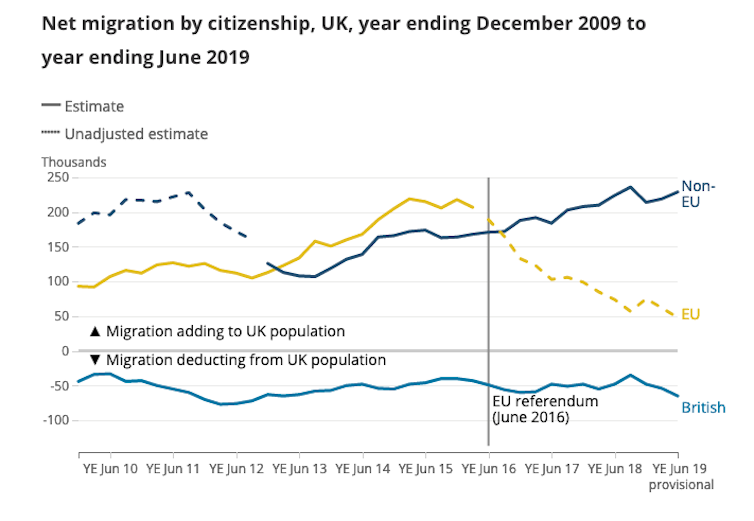

There has been a fall in EU migration since the referendum. In the year ending December 2015 there was a net gain of 218,000 EU citizens. Following a steep decline covering the time of the EU referendum in June 2016 and the immediate aftermath, the figure for the year to June 2019 was 48,000 – its lowest level during the whole of the 16 years covered by the latest ONS data.

EU immigration fell considerably during this time, from 304,000 to 199,000 per year, while emigration of EU citizens increased steadily from 86,000 to 151,000. The net decline can be seen for the EU as a whole, but is most striking for the so-called EU8 group: Czech Republic, Estonia, Hungary, Latvia, Lithuania, Poland, Slovakia, Slovenia. The UK’s net gain of people from these countries was 80,000 in the year ending December 2015, falling to around zero in the year ending June 2019.

In contrast, net migration from outside the EU has steadily risen over the same time period, from 164,000 to 229,000 in June 2019, continuing a trend which began in 2013. This has been driven primarily by an increase in immigration rather than a drop in people leaving.

While the UK is unable to put limits on the number of EU citizens arriving under free movement rules while it remains in the EU, it can control migration from outside the EU. Yet, it is this type of migration that has increased consistently.

Uncertainty in employment markets

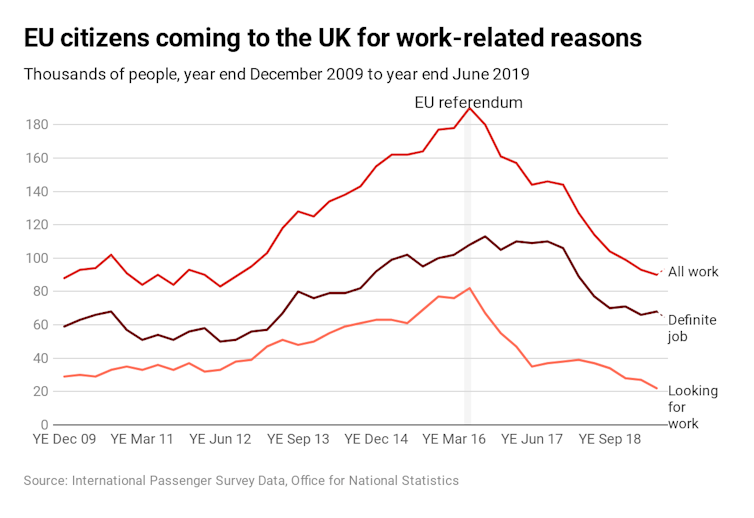

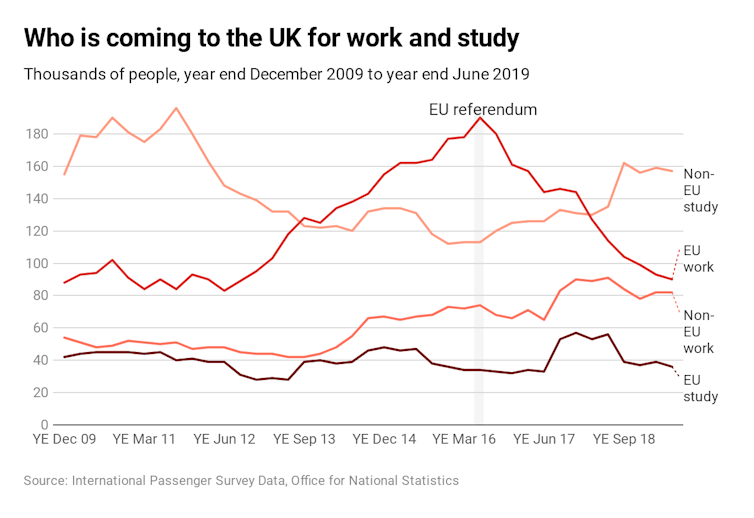

The International Passenger Survey, one of the data sources upon which the latest ONS publication is based, asks for the reasons that people migrate, with employment and study consistently the most common answers. The latest migration data reveal a decline in EU citizens migrating to the UK for work-related reasons, which include looking for a job or to take up a job offer. Work-related reasons are the most common for EU citizens, and more migrate for a definite job than to look for work.

The fall in the number of EU citizens migrating to look for a job is most apparent when comparing the year before the EU referendum against one year after it. The fall in those migrating to take up a definite job is most apparent when comparing the year ending December 2017 with the December 2018 figure. This might reflect uncertainty in the immediate post-referendum period, meaning EU citizens were less prepared to migrate speculatively but still willing to move to take up definite employment. There is consistent evidence that the number of national insurance number registrations (required to work in the UK) for EU nationals has been falling since a peak in 2015.

Attraction of British education

For migrants from outside of the EU there was a similar decline in the number of immigrants looking for work over in the three years since June 2016 (from 24,000 to 8,000), largely driven by a more restrictive migration regime. However, the numbers migrating for a definite job increased from 51,000 in the year to June 2016 to 74,000 in the year to June 2019.

Among migrants from outside the EU the most common reason for migrating to the UK was to undertake formal study – with the number giving this reason up from 113,000 in the year to June 2016 to 157,000 in the year to June 2019. This rise, combined with the rise in those migrating for employment has contributed to the net gain of migrants from outside the EU.

Given that international students generally stay in the UK for a defined period of time while studying for a course, there was considerable debate about if students should be included in the governments now abandoned net migration target. However, the debate will continue if similar targets are pursued after the 2019 election.

Where are British citizens going?

Net migration for British citizens remains fairly stable, with a net loss in each of the past 16 years. So where do these British citizens go? This is a surprisingly difficult question to answer comprehensively as the data are not routinely collected, rather estimates are constructed from various sources.

In 2006, the Institute for Public Policy Research, drawing on individual country census and other data sources, reported that around three quarters of all Britons living abroad live in 10 destination countries: Australia, Spain, US, Canada, Ireland, New Zealand, South Africa, France, Germany and Cyprus. An update in 2008 showed that UAE and Switzerland had taken Cyprus’s place at number 10.

Recent research published by demographers Guy Abel and Joe Cohen broadly confirms the top nine destinations using 2010 data, although Italy comes in at tenth spot in their work.

An eye on the future

The latest 2018-based National Population Projection from the ONS take into account trends in migration over the past 25 years. This helps put things in to perspective, as over the longer term, trends tend to fluctuate less than in the short term, where they are influenced by events such as economic conditions or Brexit.

The principal projection has factored in a decline in net migration over the next six years, with a fall to 190,000 annually from 2025. It remains to be seen if the current short-term trend for an overall decline in net migration seen in the latest estimates will continue, or indeed accelerate depending on the outcome of the Brexit negotiations. If it does, then there is a more radical low migration projection variant, which assumes a much lower annual 90,000 net gain by 2025.

Nik Lomax, Associate professor in Data Analytics for Population Research, University of Leeds

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.